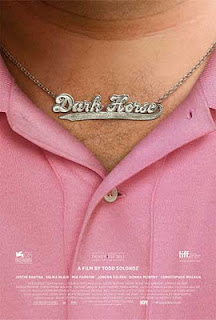

Todd Solondz's awesome Dark Horse gets its UK cinema release this week. One of my favourite movies of last year's London Film Festival, and ranked number 9 in my Best Films of 2011 list, you can read what I wrote about it here.

Wednesday, 27 June 2012

Theatre Review: Educating Rita (Richmond Theatre, & touring)

Over thirty years on from its original production, during which time it has never been out of production somewhere in the world, Willy Russell's Educating Rita remains a slight but quite delightful thing, a warm, wry two-hander that charms and beguiles even if it doesn‘t go that deep. First seen at the Menier Chocolate Factory in 2010, Tamara Harvey's brisk, enjoyable production now undertakes a national tour. And, as its memorable heroine might proclaim, it's dead good.

The story of a disillusioned Open University prof, Frank, and the street-smart, motor-mouth Liverpudlian hairdresser, also dissatisfied with her lot, whom he tutors on an Open University Literature course, Educating Rita benefits from Russell's broad but nuanced approach to characterisation and a considered but not heavy-handed approach to its themes of class, learning and self-fulfillment.

At its weakest, Russell's writing can become over-reliant on quips and one-liners. But at its best—as here—it has genuine humour and insight. Pleasingly reminiscent of Pygmalion and Born Yesterday, the play's snappy but satisfying scenes chart the shifting dynamic between Frank and Rita, the latter craving the learning that the former has pretty much decided is useless.

As the relationship between the protagonists moves between challenge and sympathy, affection and possessiveness, the two actors acquit themselves admirably. Matthew Kelly (with a haircut and beard that give him a passing resemblance to Willy Russell himself) brings humour and pathos to his rumpled, drunk Frank (booze hidden in his bookcases). Enlivened by Rita's brassy presence, he then turns sour and bitter as he perceives his influence on her to be slipping away. Kelly's work here doesn't have the surprise of, say, his amazing Pozzo in Waiting For Godot, but it's a lively, sympathetic turn, full of nice touches.

Overcoming the embarrassment of her billing as "one of the UK's best-loved personalities," Claire Sweeney makes a persuasive Rita: nicely suggesting the character's drive, her frustrations, and her pleasure in learning as she strives to transform herself into "the sort of woman who knows the difference between C S Lewis and John Lewis," or, more seriously, a woman with increased choices and options in life. It's a fresh, charming and unsentimental performance that matches Kelly's work well.

Warmly lit by Paul Anderson, and with a nicely detailed prof's office set by Tim Shortall, Harvey's crisp production moves at a clip, despite the unnecessary inclusion of an interval. Nothing is lingered over or laboured and the play's humour and humanity ring as clear as a bell.

The production tours to Cambridge (2-7 July), Oxford (9-14 July), Brighton (16 July - 21 July), and Edinburgh (1 August-27 August). Check out Mr. Russell's website for further information.

Reviewed for British Theatre Guide.

Tuesday, 26 June 2012

Last 10 Things Seen in the Theatre Meme #6

Theatre meme time again. Click on the links for full reviews.

List the last 10 things you saw at the theatre in order:

1. The Physicists (Donmar Warehouse)

2. The Drawer Boy (Finborough Theatre)

3. The Lady in the Van (Richmond Theatre)

4. Directors Showcase (Orange Tree)

5. What The Butler Saw (Vaudeville)

6. Steel Magnolias (Richmond Theatre)

7. The Cherry Orchard (Rose, Kingston)

8. The Conquering Hero (Orange Tree)

9. A Tale of Two Cities (Charing Cross Theatre)

10. She Stoops to Conquer (National Theatre)

Who was the best performer in number one (The Physicists)?

Sir John of Heffernan. And Sophie Thompson. Theatre’s best new double act!

Why did you go to see number two (The Drawer Boy)?

Reviewing.

Can you remember a line/lyric from number three (The Lady in the Van) that you liked?

“Possibly.”

What would you give number four (Directors Showcase) out of 10?

An eight.

Was there someone hot in number five (What the Butler Saw)?

Yes, there was: Nick Hendrix. A star in the making. Eden End suggested it; What the Butler Saw revealed it. (And how!)

What was number six (Steel Magnolias) about?

Why, the humour and fortitude of wealthy Southern women, darlin’.

Who was your favourite actor in number seven (The Cherry Orchard)?

Julia Hills gave great Ranevskaya.

What was your favourite bit in number eight (The Conquering Hero)?

The entirely surprising transition to the trenches at the beginning of the second half.

Would you see number nine (A Tale of Two Cities) again?

No, I don’t think I would.

What was the worst thing about number ten (She Stoops to Conquer)?

The worst thing about She Stoops to Conquer is that it’s not on any more.

Which was best?

Nothing life-changing among this set. But I had a very good time at The Physicists, Directors Showcase, and She Stoops to Conquer. And the brilliant What the Butler Saw has started me on a great big Orton binge.

Which was worst?

A Tale of Two Cities, I suppose. And, though it’s certainly not bad, high expectations led to disappointment in The Drawer Boy.

Did any make you cry?

Remained dry-eyed through almost all of these. A few predictable tears at Steel Magnolias.

Did any make you laugh?

Most of them, at some point.

Which roles would you like to play in any of them?

Alan Bennett 1 in The Lady in the Van.

Which one did you have best seats for?

The Drawer Boy, Directors Showcase, and She Stoops to Conquer.

Monday, 18 June 2012

Theatre Review: Directors Showcase - The Burglar Who Failed, Return to Sender, & Dutchman (Orange Tree)

The Orange Tree’s annual Directors Showcase double-bill turns out, this year (and to the evident confusion of some audience members), to be a triple-bill, and a rather diverse and challenging one, at that. Selected and directed by the theatre’s two resident trainees, Karima Setohy and Polina Kalinina, the three short plays whisk the viewer from a bedroom in Edwardian Wimbledon to a 1960s New York City

The evening opens comfortably enough with its lightest piece, The Burglar Who Failed by St. John Hankin, the Edwardian playwright whose The Charity That Began At Home received a proficient production by Auriol Smith at the Orange Tree at the end of last year. The Burglar... starts out like a proto-Home Alone escapade, with a pint-sized vigilante – Jessica Clark’s eager, sporty Dolly Maxwell – fending off David Antrobus’s intruder Bill Bludgeon with a hockey stick when she finds him hiding under her bed. But rather than erupting into full-blown farce and slapstick, the play takes a surprising turn, as Bludgeon confesses his distaste for his profession and the practical-minded Dolly sets about offering him career advice.

As in The Charity That Began At Home, then, Hankin both celebrates and lightly satirises middle-class Edwardian philanthropic inclinations here, and Setohy’s low-key production – though perhaps a little more static than is necessary in the second half – has genuine charm. It doesn’t add up to much, overall, but proves diverting throughout, with lovely, affectionate performances from Clark and Antrobus, and from Paula Stockbridge as Dolly’s harried, anxious mother.

Hankin’s wry brand of Edwardian empathy gets swapped for very contemporary unease in the second piece, Omar El-Khairy’s Return to Sender, a “response” to Hankin’s play that immerses the viewer in a considerably less cosy “home invasion” situation. Accomplished via a slow and superbly unsettling set-change segue, the production (also directed by Setohy) is effectively cross-cast with The Burglar Who Failed, and finds Clark brilliantly trading wholesomeness for menace as Rebecca, a teenager who’s holding hostage a well-to-do couple, Tom and Heather, for reasons that remain ambiguous to the end.

El-Khairy riffs cleverly on The Burglar... to produce a drama that touches upon a range of contemporary hot potatoes - the demonisation of youth, familial dysfunction, teenage sexuality and social inequality - while leaving plenty of space for audience interpretation. As Rebecca taunts Tom and Heather with threats of violence, accusations of infidelity and insinuations about their absent daughter Emma, the end result, as previously suggested, is more Haneke than Hankin, especially when Rebecca responds to Tom’s despairing “Why don’t you just kill us?” with the ineffably Funny Games-ish retort: “And deprive everyone of entertainment?” In addition, there’s more than a suggestion of Scorsese’s Cape Fear remake in the play’s use of a disruptive outsider figure to pick away at a middle-class family’s facade of respectability.

The writing isn’t always inspired (“You’re boring me!” shrieks Tom, unaccountably, to Rebecca at one point) and the pay-off lacks punch. But Setohy’s production retains a taut intensity, and is punctuated by nicely-judged moments of gallows humour. There are memorable jarring details, too - Rebecca’s knowledgability about classical music, for one - in a play that expresses a great deal of scepticism about how well we can know others, whether strangers or those allegedly “closest” to us.

A final disquieting encounter plays out in Kalinina’s expert production of Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman which, opening to the strains of “Sinnerman,” presents a provocative parable of American race relations. Written in the early '60s, at the height of its author’s embracing of Black Nationalism, and hailed by Norman Mailer as “the best play in America,” Baraka’s drama focuses on the meeting of a white woman, Lula (Sally Oliver), and a middle-class black man, Clay (Paapa Essiedu), on a subway car (nicely rendered in Sam Dowson’s clever design). It’s an encounter that moves from playful flirtation and sexual interest to a highly-charged exchange of racist invective (some of which elicited gasps of shock from certain audience members). “We’ll pretend that you’re free of your history... and I’m free of mine” suggests Lula. But the impossibility of such a pretence is Dutchman’s thesis, as the two protagonists find themselves unable to extricate themselves from the script of American race and gender roles.

Given that the play is, in Baraka’s terms, about “the difficulty of becoming a man in America [where] manhood – black or white – is not wanted” it’s not surprising that the characterisation of Lula is decidedly problematic. A flagrant sexual tease, neurotic liar and racist, the character doesn’t just represent “the spirit of America” she’s also Eve, and arrives bearing a whole bag full of apples as she attempts to tempt Clay out of his assimilationist stance. Oliver overcomes the crassness of the characterisation with a full-on physical performance that’s brave and striking, and she’s well-matched by Essiedu who brings wry humour and watchfulness to Clay as well as a captivating ferocity to the character’s explosive tirade at the end.

Brash and Beat-influenced, punchy and pushy (small wonder that this is a play that found favour with Norman Mailer!), Baraka’s highly mannered dialogue is American to the core – but there’s no disputing its charge and vigour in performance. The pessimism of the playwright’s vision in Dutchman – in which relationships between blacks and whites are presented as a cycle of acrimony and violence that’s destined to repeat itself, ad infinitum – is hard to take. But, buoyed by its vivid performances and boosted by the intimacy of the Orange Tree’s space, Kalinina’s production flies.

Film Flashback: 20 Years of Paradise (Donoghue, 1991)

I can hardly believe that it’s twenty years ago this month since I first saw Mary Agnes Donoghue’s Paradise in the cinema. Alongside Home Alone (1990) – my first big film obsession – Paradise was the movie that I returned to most frequently throughout the 1990s. And while other, somewhat similar films that captivated me at the time (such as Howard Zieff’s My Girl [1991]; oh, the exquisite trauma of Master Culkin’s death-by-bees!) have pretty much fallen by the wayside now, Paradise is a film that I continue to hold in high esteem and to experience with enormous gratitude, affection and pleasure. An adaptation of Jean-Loup Hubert’s Le Grand Chemin (1988) – and one that gives the lie to the received wisdom about the “inevitable” inferiority of Hollywood remakes of French films – Paradise concerns the summer spent by a shy city boy, Willard (Elijah Wood, in pre-Hobbit days, and giving a wonderfully soulful, understated performance), in the rural Michigan home of his mother’s friends Lily and Ben Reed (Melanie Griffith and Don Johnson), a couple numbed by and still grieving the death of their young son in an accident several years previously. Throughout the summer, Willard’s presence acts as a catalyst for the almost-estranged couple’s gradual reconciliation, while his friendship with the Reed’s neighbour Billie Pike (Thora Birch) gives him the courage to face his own fears and problems with greater fortitude.

What I responded to so intensely in Paradise as a 12-year-old is difficult to recall precisely. But I do remember experiencing an immediate sense of identification with the movie’s characters, who seemed entirely authentic to me, and whose concerns and dilemmas echoed my own in ways that have become increasingly clear to me as time has gone on. The key to the film is, I think, precisely the sense of intimacy it creates: Donoghue keeps the characters close to us, so that their shifts in perception, the gradual connections they forge often in spite of themselves, really resonate.

Paradise renders these small moments of connection with magical tenderness, but without an excess of sentimentality. The potential mawkishness of the material is sidestepped, throughout, with consummate delicacy and discretion, and with humour too (much of it courtesy of Sheila McCarthy’s turn as Billie’s husband-hunting waitress mother). There’s a gentle, easeful flow, and a lovely sense of structure, to the movie, but it has loss right there at its centre and a scene of confrontation between Ben and Lily (beautifully played by Johnson and Griffith, who draw effectively on their off-screen history together) that’s shocking in its intensity. (This is also the last film in which you get to see the pre-surgery Griffith looking like herself on screen and what a lovely, unique presence she is here.) I see Paradise now as a transitional film, in the sense that it bridged the gap between kids’ movies and adult cinema for me; indeed, the gaps and parallels in adults’ and children’s emotional experience of the world is one of the film’s major concerns. Given her exquisite work here, it’s a real shame that Donoghue never got the chance to direct another movie. Still, at least there’s always the opportunity – one I intend to take up quite soon, in fact – to return to Paradise.