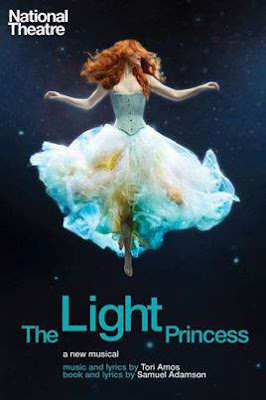

Jerry Springer: The Opera, London Road, the sublime Caroline, or Change: the musicals staged at the National Theatre during the reign of Sir Nicholas of Hytner have all been, in different ways, radical, challenging affairs that have stretched the form in new directions - a deliberate attempt, it would seem, to get away from the cosier, Broadway-leaning inclinations of Trevor Nunn’s tenure as artistic director of the theatre. The Light Princess, Tori Amos and Samuel Adamson’s swooningly ambitious adaptation of George MacDonald’s 1864 fairy-tale, demonstrates once again Hytner’s commitment to creative, non-conservative musical theatre programming. This much-anticipated show – the first foray for both writers into the musical genre – has been long in development, as my two interviews with Adamson (here and here) attest. But, on the evidence of last night’s staggeringly confident and rapturously received first preview, it’s been worth every single second of the wait.

Taking MacDonald’s story about a young girl cursed to have no gravity merely as their starting point, Amos, Adamson and director Marianne Elliott – herself flying high after War Horse and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time – have fashioned a fantastically fierce, fresh, frank and funny feminist fable. You won’t find an evil spinster Aunt dispensing a curse in this version; instead, this story is – true to form for Amos – more concerned with the damage Daddies do.

The action unfolds in two warring kingdoms, Lagobel and Sealand (gorgeously rendered in Rae Smith’s sumptuous design), where the teenage heirs to the respective thrones, Princess Althea and Prince Digby, have reacted to the deaths of their mothers in contrasting ways. The response of the Princess - played and sung with breathtaking passion, biting wit and luscious sensuality by the stunning Rosalie Craig - is weightlessness, which is presented here as a psychologically-motivated escape route for the avoidance of pain. In contrast, Digby (excellent Nick Hendrix: as sweet of voice as he’s buff of bicep) has become heavy-hearted and solemn in his grief. When the two meet in the Wilderness that separates their territories, a love affair ensues – one that certainly doesn’t win the approval of their fathers or the populace.

Aided and abetted by many of her collaborators on her previous NT-originated successes (including Smith, choreographer Steven Hoggett and puppetry director Finn Caldwell), Elliott makes the production another thrilling “total theatre” experience: one that’s equal parts cutting-edge and traditional. A lovely animated prelude outlines the histories of the kingdoms, but a simple sheet serves initially as a lake for our two lovers to liaise in. As per War Horse, the creatures of the kingdoms are puppets, designed this time by Toby Olié. The most graceful of these is Digby’s majestic falcon companion Zephryus (Ben Thompson); the funniest a little pink mouse who gets a mighty gross-out moment. And the Princess’s lightness is conveyed by two means, with the undulating Craig sometimes borne aloft by wires, at others by the bodies of black-clad acrobats.

You might fear (as I did) that all this activity will swamp the story. But no. The narrative feels very intricately worked out by Amos and Adamson in terms of theme, imagery and metaphor, and all the elements enlisted by Elliott contribute to its lucid, expressive telling. There are some brilliantly surreal stage pictures which I won’t reveal, but suffice it to say that the director and her team find wonderful ways to bring the story’s revision of fairy-tale tropes to life and into a contemporary teen context that still feels timeless enough, not least in a sublime scene in which Althea’s father King Darius (Clive Rowe) enlists the help of a series of suitors to bring his daughter down to earth. (As in Wicked - a spiritual sister to this show in its revisionist attitude, near-homophonous heroines and firm female-focus - a song called “Defying Gravity” could easily find a home here.)

Then there’s the music. Supple and robust, delicate, playful and strident by turns, Amos’s score is a glorious thing, intricate, demanding and complex at times, instantly hummable at others, and Adamson’s book matches it for beauty, cheek and charm. Amos’s emotional range as an artist has always astounded, and she brings that to bear here in a quirkily structured, diverse score that can move fluidly from wild humour to melancholy, from swaggering aggression to the most tender of laments, in an instant. With her regular collaborator John Philip Shenale overseeing the orchestrations, liberal use of strings and woodwind, and - yeah! - a Bosendorfer in the pit (where dynamic Music Director/Supervisor Martin Lowe can be seen displaying his customary infectious exuberance), it’s perhaps no surprise that The Light Princess is closest to Amos’s classically-inspired Night of Hunters project musically. And yet it’s totally fresh and distinctive too: Amos is in no way resting on her laurels or repeating herself. There’s a stirring soul and gospel moment here, a pop/rock flourish there, but everything feels cohesive and organic, the music emerging from the protagonists and their ever-shifting emotional states.

There are some jaw-dropping duets, not only for Althea and Digby but for other characters too: a stunning sustained sequence finds the Princess’s loyal companion Piper (brilliant Amy Booth-Steel) fiercely challenging the King for his belligerence. Disgracefully wasted in The Hothouse, the great Clive Rowe does not go to waste here as the patriarch made tyrannous by loss. At one point scarily bellowing his belief in his own authority, he later gets a standout aria that’s one of the production’s most intensely moving moments. And the contributions of an exceptionally well-drilled ensemble are also very fine.

Meanwhile, Amos’s lyrical dexterity – her delight in word play, allusion, assonance and alliteration – is also on display. Book and lyrics allow genuinely complicated emotions into them, and when Digby speaks about being indoctrinated by his father’s beliefs, one hears the voice of many Amos characters, challenging themselves to overcome their reliance upon others’ opinions and judgements. There’s a gorgeously rebellious spirit to this musical, and a clear political dimension too: here the “duties” of marriage and monarchy – as expressions of patriarchal power – weigh a girl (and a boy) down. (Which makes the conclusion, for all its cheeky twists, look a tad too conventional, it must be said.)

For those of us to whom Amos’s music has meant so very much over the years, it’s especially exciting and moving to see her venturing into this new form and thriving there. But I think it’s fair to say that even those who aren’t dedicated Toriphiles will find plenty to engage and beguile them here. “I don’t fly; I float,” Althea is given to reminding those around her. This show flies and floats. It’s an awesome achievement for all concerned and deserves to run and run.

The Light Princess is currently booking until January 2014. Further information at the National Theatre website.

Wednesday, 18 September 2013

TIFF 2013 Coverage: My Toronto International Film Festival Reviews

I was fortunate enough to be able to attend the

Toronto International Film Festival for the first time earlier this month, to

provide festival coverage for PopMatters. Below are links to my reviews of the

films that I saw at the festival:

Tuesday, 17 September 2013

Theatre Review: Springs Eternal (Orange Tree)

|

| Julia Hills and Stuart Fox in Springs Eternal (Photo: Robert Day) |

So here’s a super start to a significant season at Richmond’s Orange Tree. Sam Walters, who ends his remarkable 42 year tenure as artistic director of the theatre next year, opens his final season by directing the rather belated world premiere of a 1943 play by Susan Glaspell. Glaspell (1876-1948) is one of the (many) playwrights whose work the Orange Tree has rediscovered for British audiences; the theatre has produced a number of her plays over the years, the last being a superb take on the Pulitzer Prize-winning Alison’s House back in 2009. Springs Eternal was Glaspell’s last play and one that, for a variety of reasons, slipped through the net. It turns out to be an intriguing, character-rich piece whose humour and humanity Walters’s deft, sensitive production brings beautifully to the fore.

The play is concerned with exploring different attitudes to World War II and, in particular, generational splits and schisms in relation to the conflict. It unfolds in the boho New York State household of one Owen Higgenbothem (Stuart Fox), an academic who, some years previously, wrote a book entitled The World of Tomorrow which set out his idealistic vision of the future. Bitterly disillusioned by the advent of war, Higgenbothem has retreated into a comfortable kind of cynicism that impacts upon those around him, from his second wife Margaret (Julia Hills) to his son Harold (Jeremy Lloyd) to his housekeeper Mrs. Soames (Auriol Smith) whose own son, Freddie, is fighting in the Pacific.

Glaspell clutters her scenario a tad - there’s an apparent aborted elopement and some complicated family dynamics that take some working out – and she clearly enjoys her characters’ interactions so much that she’s occasionally a bit indulgent with them; in particular, some windy musings in the second half could have been snipped. But gradually the drama’s concerns come into focus. Quirkier in tone than much of Glaspell’s work, the writing here sometimes has the wonderful loopy lyricism of a John Guare. “He has made my love ridiculous!” wails one character, to which another replies: “He didn’t mean to. He has the flu”, and the actors clearly relish the original opportunities provided for them.

Indeed, the production boast several performances that it’s worth travelling many miles to see. Julia Hills is terrifically sympathetic as the put-upon Margaret; a fierce late scene in which she expresses her feelings of anger and resentment at Owen’s attitude proves a pivotal moment. Miranda Foster does a delicious gem of a comic performance as his slightly batty first wife, whether moved by her own memoirs or pausing, apropos of nothing, to muse: “Why haven’t I seen more of Africa?” Rosy-cheeked Jeremy Lloyd is adorably earnest as the self-reliant conscientious objector son dealing with his father’s disappointment and disdain. And Auriol Smith works wonders as the house-keeper whose common sense pronouncements cut through the intellectual posturing of her employer. This isn’t Glaspell’s most perfectly constructed work, but Walters’s production makes it an exquisite, involving evening overall.

The production is booking until 19th October.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)