"Films that stretch your mind and heart ...that make you think and feel in a way that you haven't before." Such was Maggie Gyllenhaal's definition of what she, as a Cannes Main Competition juror, was looking to see at the Festival this year, as the event returned to its first post-pandemic (sic) edition.

Many of the films featured at this year's Cannes turned up in the diverse, expansive programme of Wrocław's New Horizons, along with some choice selections from Berlin, Sundance, and elsewhere. These films were presented alongside New Horizons' own world premieres, exhibitions, and carefully curated retrospectives, which this year were dedicated to, among others, Chantal Akerman, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Gaspar Noé, the latter of whom was present - to considerable fanboy fervour - at the festival.

|

| Gaspar Noé with another star: Sebastian Smoliński |

I haven't attended New Horizons since 2016, the year in which Wrocław was joint European Capital of Culture, and it was heartening to find the event retaining its distinctive identity and vibe as it reaches its 21st edition. However, despite the promise of the programme, and the collective joy of returning to the big screen (which felt freshly encompassing, expressive and overwhelming after so many months away from it), many of the new films I saw turned out to be draining disappointments.

The first let-down came with the first film I caught: Xavier Beauvois's Albatros (Drift Away). Beauvois's drama starts wonderfully, sketching out the domestic and professional life of a small town gendarmerie commander (the great Jeremie Renier) in an intelligent, quietly absorbing series of scenes that inspired me to scrawl "I LOVE THE FRENCH!! " across my notepad.

But just as the scenes seem to be building towards a portrait that's at once collective and deeply personal, the fallout from a shooting incident sends the plot on a downward spiral from which it never recovers. The kind of narrative shift that John Sayles pulled off so powerfully and meaningfully in Limbo (1999) is botched by Beauvois, as the film turns into a painfully limp man-in-peril-on-the-sea quest. By the time Albatros reaches its predictable and sentimental conclusion the only surprise offered is that a film that started out so smart could end up so dumb.

For me, Albatros set an unfortunate precedent for many of the films at this year's festival, in which a promising premise or first half often gave way to a compromised or lacklustre development. This was true of such shakily-executed meta-exercises as Mia Hansen-Løve's Bergman Island and Nadav Lapid's Ahed's Knee, the latter's hectoring tone and stylistic inconsistencies constituting a particular disappointment after Lapid's sensational Synonyms two years ago.

Established auteurs often seemed to be treading water, or skirting dangerously close to self-parody in their approach to familiar themes. Apichatpong Weerasethakul's latest, Memoria, held together for at least some of its running time by Tilda Swinton's presence in the lead, was a case in point, sinking into numbing, half-baked abstractions in its final stages. Asghar Farhadi's A Hero, while substantially superior to The Salesman and Everybody Knows, found the writer-director offering yet another highly-strung social melodrama based around an increasingly unlikely pile-up of deceptions.

Gaspar Noé's Vortex seemed to offer something quite different to his past provocations, but this split screen portrait of illness and decline featuring Françoise Lebrun and (yup) Dario Argento as a married couple becomes grindingly monotonous, entirely lacking the kind of feeling and insight that made a similar work like Tom Browne's Radiator resonate. Another film on the topic of mortality, François Ozon's Everything Went Fine, based on his frequent collaborator, the late Emmanuelle Bernheim's, autobiographical book, was far more palatable, and boasts fine performances from Sophie Marceau and Andre Dussollier. But, as indicated by the blithe title, this measured, sane look at dealing with a loved one's desire to die has turned out a shade too measured and sane to generate much interest or emotional impact.

I also failed to share the love for Radu Jude's Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn in which po mo formalist playfulness and habitual snark are mobilised for a take on a contemporary moral panic about a sex video gone viral. As one of the first films to directly address Covid reality, Bad Luck Banging initially has a fresh, uncanny quality as it tracks its masked heroine (Katia Pascariu) through the Bucharest streets in the opening sections, the camera gleefully capturing foul-mouthed confrontations or else getting distracted by kitschy billboards. But, following an intermittently hilarious A to Z mid-section, the tedious third act reveals its hand too openly. Pitting its sane, intellectual heroine against a bunch of conveniently moronic, self-righteous and hypocritical accusers, Jude's film merely panders to liberal groupthink and ends up insufferably smug.

At the opposite end of the scale in terms of humane vision, and with its own understated corona coda, was Ryusuke Hamaguchi's Drive My Car. Adapted from a Murakami short story, the film focuses on a cuckolded, widowed actor gradually making contact with the world again as he undertakes the direction of a production of Uncle Vanya. Mostly absorbing - especially for those of us compelled by rehearsal processes and actors' interactions, which the film renders perceptively - the film loses a lot of goodwill in its third hour, resorting to spelling out in confessional monologues the emotions that have been delicately suggested before, and also succumbing to a flagrant plot contrivance in order to bring about its hero's return to the boards.

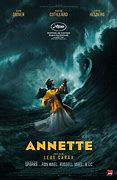

The only auteur to truly be firing on all creative cylinders was Leos Carax whose divisive Sparks-scored musical extravaganza Annette, with its daring transitions, formal finesse, intelligent merging of theatrical and cinematic techniques, and piercingly moving climax, is one of the few films featured at the festival that I would want to watch again.

The work of new directors also yielded mixed results. Despite striking moments (and strong performances from Charlie Shotwell and Jennifer Ehle), Pascual Sisto's debut feature John and the Hole, described as Home Alone meets Haneke, emerged as studiedly affectless, while Déa Kulumbegashvili's passive aggressive, bizarrely overpraised Beginning ultimately played out as little more than a Slow Cinema pastiche.

The Cannes Palme winner (and NH opening night film) Titane was another film that failed to make good on an explosive opening. Highly derivative of Claire Denis and David Cronenberg, Julia Ducournau's genderqueer fantasia, about a serial killing dancer passing herself off as the lost son of a lonely fireman (Vincent Lindon) after impregnation by automobile, ticks off modish themes with the calculation of a dilligent MA student writing a thesis proposal on transhumanism. I found the film abrasive to begin with and surprisingly sentimental to end, and full of plot holes big enough to drive a tanker through. But there's no denying the power of Agathe Rousselle's protean presence in the lead, or the film's status as a tailor-made cult item.

Among a small selection of Polish productions that I saw (more of those in a couple of weeks in Gdynia...), Grzegorz Zariczny's Simple Things and Piotr Stasik's The Moths were notable for mobilising the idea of therapy workshops in very different contexts. The notion seems little more than a garnish in Simple Things: the primary focus of this modest, engaging docu-fiction is the everyday experiences of a couple, Błażej Kitowski and Magdalena Sztorc, moving from Warsaw to renovate a country house, with some unexpected, but emotionally challenging, assistance from Błażej's uncle (Tomasz Schimscheiner). Lovingly photographed by the talented Weronika Bilska (DoP of the wonderful Everyone Has a Summer) the film unfolds in a natural, unforced way that proves beguiling.

The Moths, on the other hand, is hyper from the get-go. Stasik's film is a highly stylised riff on Lord of the Flies in which a group of gamers turn feral in the woods before returning to enact their various traumas via performance workshops. Occasionally frustrating and heavy-handed in its symbolism, the film is nonetheless consistently arresting: a challenging sensory experience that builds to a delicate, cathartic coda.

The Polish premiere destined to make the biggest splash, however, was Piotr Domalewski's Hyacinth, a Netflix-produced thriller featuring Domalewski regular Tomasz Ziętek as a detective investigating the killings of several gay men in 1980s Warsaw (a period and location expertly evoked via Jagna Janicka's fine production design and Ola Staszko's costumes).

Marcin Ciastoń's smart script (which includes one Poland-baiting epigram that drew a hearty round of audience applause) fully embraces its murky cop procedural genre mode. But the film gains extra bite from its context, highlighting the persecution of homosexuals in the Poland of this period in a way that complements Tomasz Jędrowski's recently-published novel Swimming in the Dark, and suggests an overdue popular focus on the history of Polish LGBT experience.

Following so many under-written, plot-lite endurance tests at the festival Hyacinth's narrative drive and engaging characters were certainly appreciated. Overall I saw little to really "stretch the mind and heart" at this particular edition of New Horizons, but Domalewski's film is certainly one to discuss in more detail when it hits Netflix in the Autumn.